Why is a Steampunk like a Magician?

This is not a Carroll-esque Mad Hatter’s riddle. (Probably.) It is a question posed with at least some seriousness. And, unlike the Hatter’s question, this one has an answer.

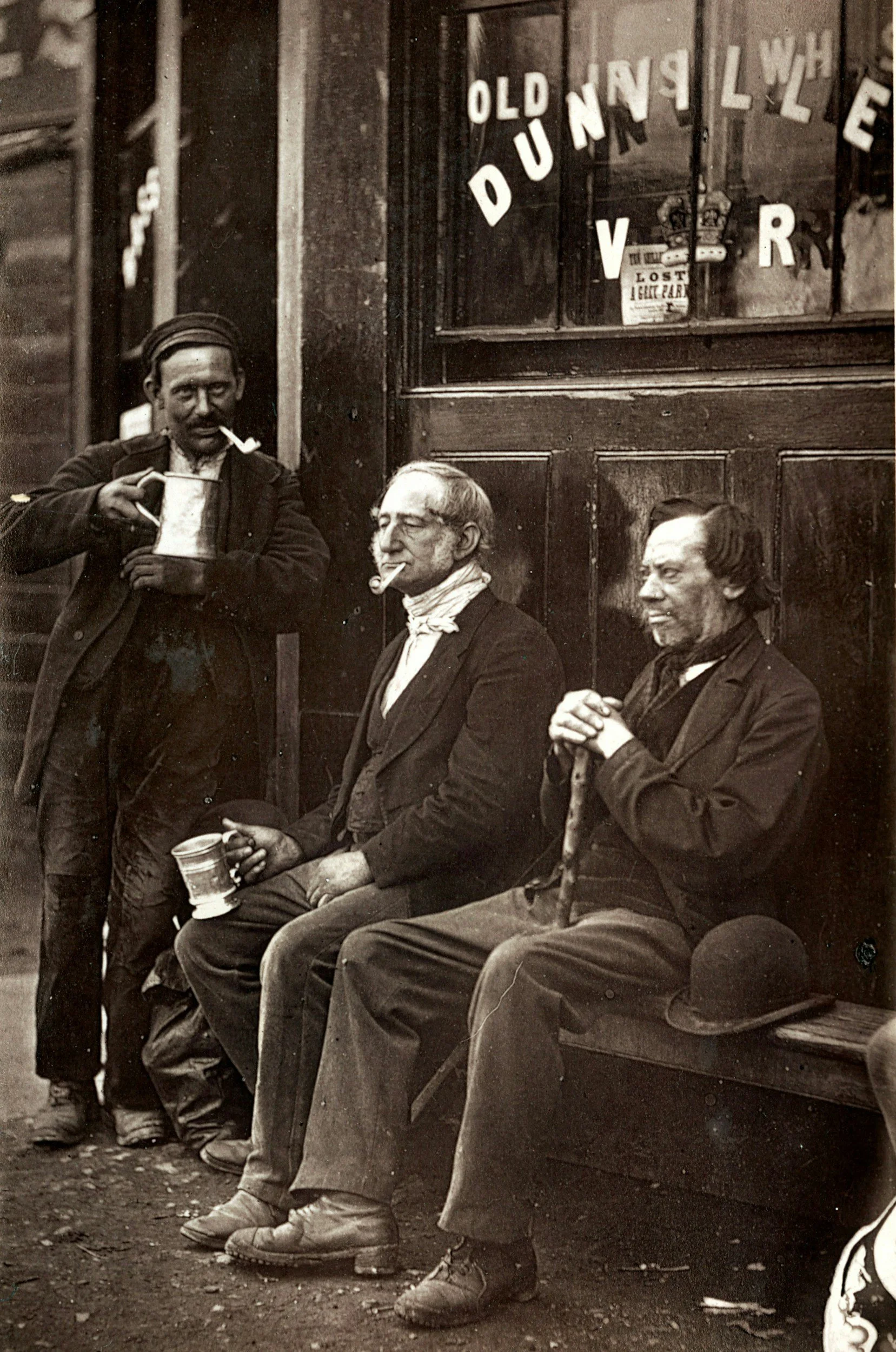

Steampunk began as a literary genre and has since become a subculture of Victorian retrofuturistic aesthetics. Steampunk, and elements thereof, can be now found not only in books, but also in film, TV, graphic novels, music, convention halls, picnics in graveyards, sipping at tea houses, or simply by walking down the street. The aesthetic nature of Steampunk, over and above its literary origins, has become one of its defining characteristics.

While there is always an underlying “Victorian-y” aesthetic, the way that manifests is as plentiful as are Steampunks themselves. And while aesthetics usually focuses on how things look, it needs not be limited to such. We see this today in the various “-cores”: cottagecore, goblincore, cluttercore, and so on, as well as other aesthetics, like dark academia. Yes, they have a look to them, and that look is important, but they also rely on textures and scents. It is not just the green of the moss, but its feeling under one’s fingers or feet and the scent of it in the air that is important. Aesthetics are, or can be, massively multi-media and include visual, tactile, audio, and visual elements; and we see this in Steampunk—and magic—alike.

In Steampunk, there are any number of visual delights to behold. The color of fabric, the swish of a kilt, the shininess of brass, the smear of grease across an airship crewmember’s forehead or overalls, or the flick of a fan. However, when Steampunks gather (be it at a convention, invading a museum or zoo, or meeting for lunch at a tearoom), there is more going on than just what is visible. At a convention, for instance, one may hear the soundtrack of steam engines, smell delightful dishes from the tea room and feel fine china teacups, catch the scent of leather from hats and harnesses, hear live performances by musicians, or listen to an author, dressed in their Steampunk finery, read from their latest work. The Steampunk experience can surround you in every way imaginable.

An increasingly common element of Steampunk culture, especially at conventions, is the development of a “Steamsona,” or the Steampunk’s persona. Steampunks tend to have their own particular look, and for many, that look comes with a backstory, which becomes the backbone of their Steamsona. For some, this is little more than a name and being a member of an airship crew, a common form of a Steampunk club. For others, it’s a deeply developed history, with explanations for every facet of their Steamsona’s appearance and behavior: this medal is from that order of (usually fantastic) knighthood, this sash represents their peerage, that weird looking thing powered by a tube of bubbling green…something is used to tune the phlogiston engine of the Airship Enochiana. Names, titles, family background, notoriety—all of these things can figure into the person one becomes. For many, this is but a fun exercise to give their Steamsona some fit and flair, but is discarded to be “out of character” at any given moment. For others, that character is who they are for the length of the con, and sometimes beyond.

What does any of this have to do with magic? There is the so-called genre of “gaslamp,” which is supposed to be somehow different from the genre of Steampunk while sharing the exact same sense of Victorian-y aesthetics, but also with magic. As one might imagine, the magic found in this form of Steampunk is typically of the fantasy variety. But it also fits in perfectly with Steampunk’s overall presentation. The magic of Steampunk is no more over-the-top than is its “science.” There is nothing stranger in hurling a fireball down Main Street than there is in blasting a phlogiston-powered ray gun down the same street.

But, like the rest of Steampunk, Steampunk-styled magic isn’t just about the end results, it’s also about getting there in style. A Steampunk’s magical accoutrements can reflect the same Victorian aesthetics as does everything else Steampunk. That can be spats embroidered with designs from the Key of Solomon, a golden Eye of Horus on one’s hat band, a corset with scrawled over with Theban, or a parasol with a talisman to keep away the rain. Some magical paraphernalia, such as a brass flame-headed magic wand, isn’t even particularly far beyond what an actual Victorian-era magician might have had.

The Victorians were great “borrowers,” let’s say, of the past. The use of various shapes (in the form of pentacles, magic squares, and various geometric designs) can be easily traced to at least to the fifteenth century in the so-called “learned” magic of Europe that required one to be able to read. The use of different stones and gems, the color of which was often important, as well as different metal, goes back much farther, from the tenth century Picatrix, the ninth century De Imaginibus, or their sources in the second through fourth century writings of the Hermeticists and Neoplatonists, and their sources from Alexandrian Egypt, and so forth. That is to say, magic has always had an aesthetic element, and, with very few exceptions, that element has been important to the magic itself. But the practice of magic was, and is, also an aesthetic experience, whether it is the “smells and bells” lauded by many ceremonial magicians or the feeling of nature beneath one’s feet in modern Pagan practices.

But as much as they might have been steeped in the past, they always had an eye fixed on now. Something that caught the eye of a number of Victorian occultists was the new science of psychoanalysis, especially the works of Carl Jung, as well as a plethora of other psychological theories. From this the idea of the “magical personality” or persona began to form. Dion Fortune, in her novel Moon Magic, of this wrote:

A magical personality is a strange thing. It is more like a familiar than anything else, and one transfers one’s consciousness to it as one does to an astral projection, until finally one identifies oneself with it and becomes that which one has built. (p. 51)

Part of how this persona is built is through the aesthetics of magical practice.

Arguably, one of the more persistent elements of Victorian and descended occultisms is its physical culture(s). The Victorians loved their stuff, and those who had the means to make that stuff not just fancy but pretty did so. This carried over into the world of magic. Much like Steampunks, Victorian and Edwardian occultists surrounded themselves with bits and bobs of symbolic significance. Masonic-style aprons were used by Freemasons, Martinists, and Rosicrucians alike. There are sashes of different colors and imagery denoting grade or rank within an order. The style, color, or symbols upon a robe might designate rank, order, or ritual office. Colored candles take on a symbolism that connects them to the powers of the cosmos. There was music, chanting, and speeches to educate an initiatory candidate or call upon spiritual aid. Incense, perfumes, scented oils, water and wine, magical names and titles; all these were common to the world of the Victorian occultist and to many occultists today. Every portion of it was meant to inform the practitioner of their place in creation, not simply as an everyday person, but as someone who could command the very elements of that creation to do as they will. Magic, like aesthetics, is often massively multi-media. It is meant to surround and interpenetrate the practitioner, and through these means does one identify with, and become, the magical persona which they’ve built, as Fortune wrote.

Of course, not all Steampunks or occultists engage in this. But for those who do, this is why a Steampunk is like a magician. Both use their environs, clothing, scents, textures, sounds, and anything else that might come to hand to transform themselves into someone else. None of this is new. We have been creating ourselves, or at least attempting to, for most of our lives. What differs is the concentration of intent—of one’s Will, we might say. For both the Steampunk and the magician, it is more than a vague “this is what I want to be when I grow up.” It is the envisioning of a specific, often highly detailed, being, and saying that is what I am going to become.

Check out Jeffery’s book, High Magic in the Age of Steam, below.